Introduction

Since MBC’s inception in January 2018, the team has worked tirelessly to document, archive and visualise the history of detention camps in Kenya setup by the British colonial government during the state of emergency (1952-1960). We have approached this subject not as experts but as learners who through our exploration, determination and discovery have set out to share what we find in a variety of ways and formats.

Our primary tools of trade have been digital platforms. Some of the ways in which we have employed digital methods are:

-

Oral history recordings and testimonies

-

Documentaries

-

Photography

-

Interactive digital maps

-

3D reconstructions

Why digital?

We see digital tools and media as a way to reach wider audiences in different geographic regions and communicate to audiences at different levels of literacy, expertise and age.

As a volunteer organisation working across Kenya and the UK, a digital approach also allows us to share our work without having to occupy physical space or possess physical collections.

Digital reconstructions as an ongoing process

We present these digital reconstructions not as final outputs but as initial visuals that can help us generate and continue conversations on the presence of detention camps in Kenya during the colonial period.

Our initial aim was to create reconstructions of how entire camps would have looked during the colonial period and present a complete visualisation of the same. We soon realised this would be an uphill task, given that we are dealing with multiple historical sources and multiple structures in multiple locations.

Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, we realised that presenting final, unquestionable visualisations is not the approach we want to take. We see digital as an incremental process, one in which we can be open about the information we have so far and that which we don’t.

We steer away from a need to present finalised, complete digital reconstructions as experts and we instead embrace the reconstruction process as a way to communicate step by step progress in our research and findings. Today we reconstruct one building, tomorrow we reconstruct the next, and step by step we begin to visualise entire camp sites.

To start with, we picked individual structures from two different camps in Nyeri county, Mweru and Aguthi. We created digital models of each site based on remnants of the same structures today, visual archival sources and oral history testimonies from Mau Mau veterans

The 3D models presented are singular buildings from each site. The structures we present here were picked due to the presence of strong research evidence to support their visualisation as outlined below:

Aguthi Camp

Entrance and Gate

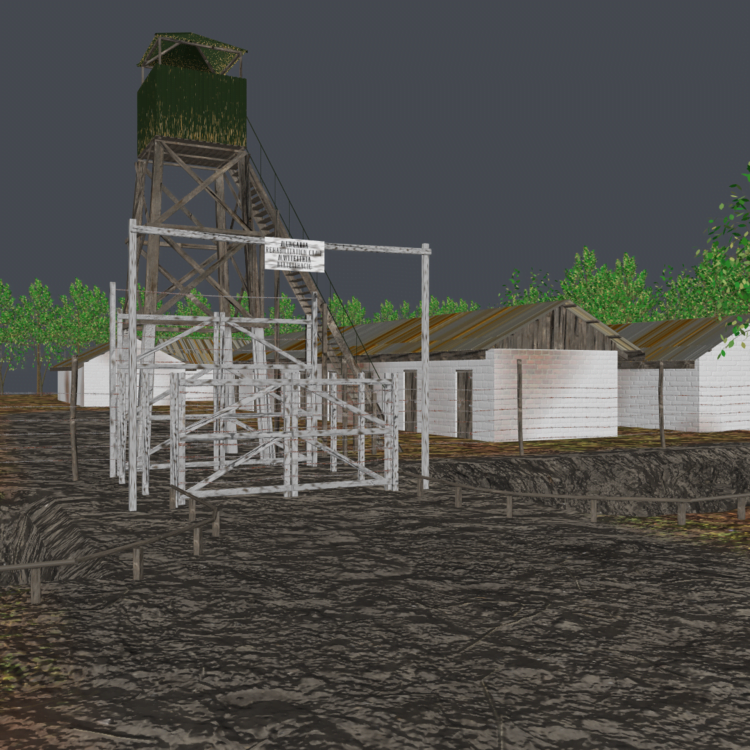

The reconstruction of the Aguthi camp entrance was based primarily on archival resources. In the course of our research, we found two different photographs of the Aguthi camp entrance taken during the Emergency (1952 – 1960).

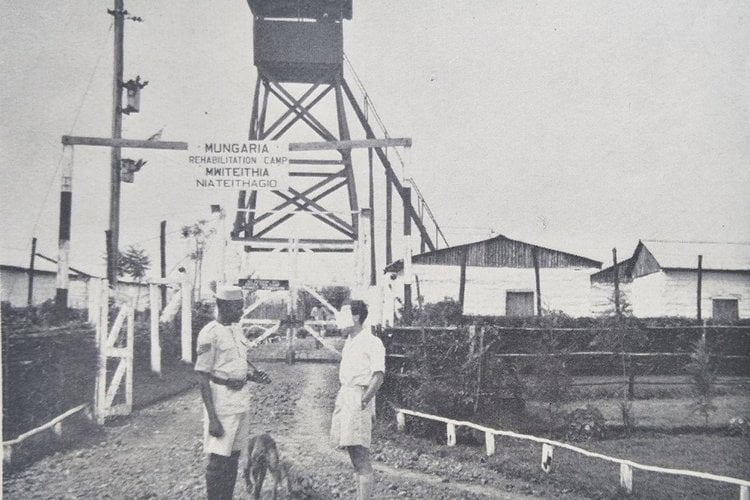

Figure 1: Aguthi Camp entrance – Taken from J.M Kariuki Mau Mau detainee, date unknown.

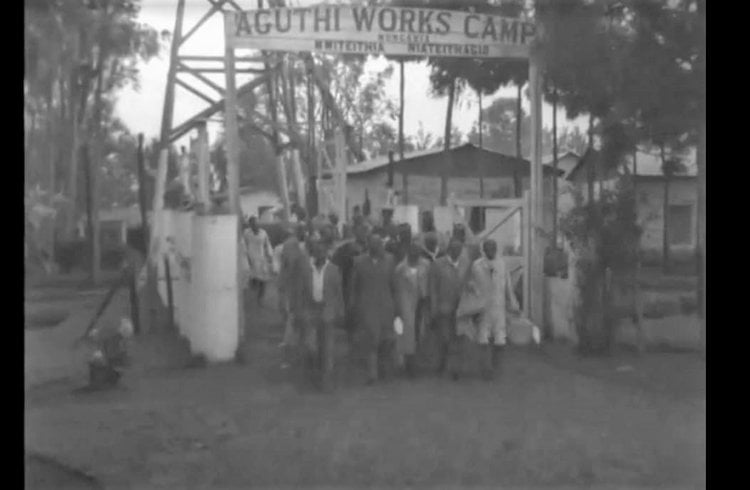

Figure 2: Aguthi Works Camp entrance, screen shot from British Pathe video, 1959

Both sources show different signs at the entrance to the same camp, however we know that this is the same place by analyzing the buildings in the background and the position of the watchtower in relation to the background buildings. Additionally both archival photographs reference the same location, i.e. Aguthi Works Camp, also known as Mungaria Works Camp.

We believe that the photo presented by JM Kariuki was taken much earlier (by comparing the vegetation/trees around), probably during the early stages of the emergency. While the photo from the British Pathe video lists the date of recording as 1959, shortly before the camp was closed.

Instead of reconstructing the gate based on only one of the photos, we reconstructed both gates with both signs.

Figure 3: Aguthi Gate Version 1: based on archival photo from JM Karikuki’s book

Figure 4: Aguthi gate version 2: Based on British Pathe video

Solitary Confinement Cell

The solitary cells found in Aguthi camp were small rooms approx. 11ft by 10ft. The structures had no windows, no natural light and had barbed wire along the roof lining to prevent detainees from escaping or attempting to escape. After independence, Aguthii Works Camp was turned into a secondary school (Kangubiri Girls High School). The buildings still remain to this day and are used by the school as stores.

From our conversations with the local community, we were able to gather that the school (Kangubuiri Girls) had not altered the original buildings of the cells significantly.

The school caretaker mentioned that originally the door had three peep holes at the top so that camp officers were able to look into the cells. But the school had turned the doors upside down during renovation. Aside from this modification, the buildings exterior was painted to match the school’s theme.

Figure 5: Solitary cell building reconstruction

Solitary cells as they appear today in Kangubiri Girls High School (formerly Aguthi Works Camp). They are presently used as stores. Notice the doors turned upside down.

Mweru

Torture chamber

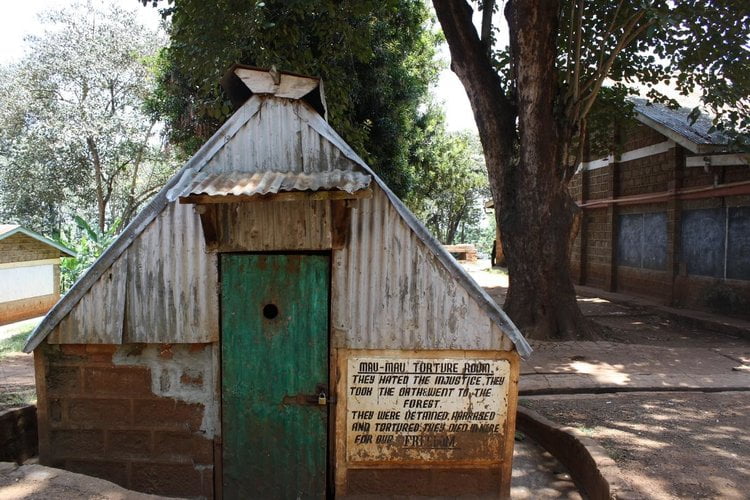

The torture chamber in Mweru was a solitary cell where detainees would be held for extended periods of time, beaten, tortured and denied food and movement. The building is positioned centrally within Mweru high school and has remained almost entirely unchanged since colonial times. One notable addition is the erection of a sign board by the school which reads “Mau Mau Torture Room, they hated the injustice, they took the oath and went to the forest. They were detained, harassed and tortured, they died for our FREEDOM”

Figure 6: Former torture chamber Mweru camp as it appears in present day Mweru High School

Figure 7: Reconstruction of torture chamber in Mweru camp

Mass cell

Mass cells in Mweru camp were 17ft by 28ft buildings that could possibly hold up to 60 people. The buildings themselves had only one entrance, no windows and barbed wire along the roof to prevent detainees from escaping.

Evidence for the reconstructions of the mass cells in Mweru primarily came from existing buildings present at the site today (which have remained largely unchanged) and oral testimony from individuals in the local community.

Figure 8: Mass cells (Mweru works camps) today used as classrooms in Mweru High school

Today these buildings are used as classrooms and you can see that the school carved out windows from the brick wall to provide ventilation. However, the barbed wire evidence still remains.

Figure 9: Interior of class room, notice barbed wire along the roof. Mweru High school.

Oral testimony from local community also drew our attention to the fact that the original cell structures did not have windows, while the present-day structures which are used as classrooms do. This has been factored into the digital reconstructions as shown below.

Figure 10: Reconstruction of Mass cells in Mweru Camp

Questions we are exploring through this reconstruction process

How do we communicate and visualise uncertainty?

Given that we are working with different sources of information (i.e. oral history, archives, existing remains), we are piecing different bits and pieces from each information source to try and form a larger picture of how the camps might have looked.

Yet despite having multiple sources of historical information, these sources each have significant gaps, in part due to:

-

The destruction/migration of archives

-

The suppression and erasure of this spoken and written history in Kenya

-

The modification of camp buildings to suit different purposes today.

As a result, each source of information is incomplete on its own and as we bring each of them together, we know that reconstructions will never be 100% accurate. This is especially true given how likely it is that structures were altered throughout the course of the Emergency.

The challenge for us then is how do we visualise or communicate these levels of uncertainty within the reconstructions?

How do we make technical aspects such as 3D visualisation and 3D reconstructions open and community friendly?

The decision to visualise these detention camps, primarily stems from a need to create public awareness and engagement with the history of these camps both in the UK and in Kenya.

However, the process of 3D reconstruction itself is a highly technical process that can create a form of exclusion between audiences or community members who do not understand what 3D is or why 3D?

This may in turn, alienate audiences and prevent community members from participating. It also risks positioning technical experts as knowledge producers whose work process is final and cannot be questioned.

Instead of seeing the community as consumers of the final digital output, we envision them as being active participants in the decision-making process towards visualising this aspect of colonial history.

To support this aim we are exploring a number of options such as:

-

Holding community workshops where we can invite the public to explore, engage, challenge and contribute to the reconstruction process

-

Being entirely transparent about the decisions made within the reconstruction process and all the research sources we have used.

-

Expanding the relationship between the physical and digital. An example of this would be printing the 3D models so that those who are unable to interact with digital data can interact with physical representations of the digital models.

-

Working with university students from different disciplines to explore creative and alternative ways of using the data.

Another major thing to consider is that we are also speaking to Mau Mau veterans now in their 70’s, 80’s and 90’s. This difference in age and technical awareness can create a gap between the work we produce and the people who help us produce it.

Questions to consider in this regard :-

-

How do we communicate to older generations what we are doing and the datasets we are creating?

-

What language do we use to describe the technical nature of the work i.e. How do we phrase words like 3D reconstructions?

-

How do we demonstrate the relationship between the information shared by veterans and the outputs and visualisations we create?

How do we combine tangible and intangible histories through digital media?

We believe that in themselves digital reconstructions paint an incomplete picture if they are not contextualised by the tangible and intangible histories they are inextricably linked to.

-

How do we incorporate the memories, the experiences, the emotion attached to these histories into digital media and digital experiences?

Crowdsourcing can be seen as a form of co-production and source for intangible heritage by allowing audiences to participate in the telling of narratives and provision of context.

-

How can we therefore incorporate crowdsourced information into digital platforms? This can decentralise an expert role primarily belonging to the institution by generating new information resources that were previously overlooked or had no way to be captured.

Moving forward

These digital reconstructions are just the beginning. The questions presented above continue to inform our work on these sites moving forward. In our first attempt to create and present them, we open up these data sets to public exploration and engagement. We know there are questions we haven’t thought of or angles we haven’t explored and we invite you to share these with us, to create an open, iterative approach to digital reconstructions.

If you are interested in learning more, please visit the website of our partner, African DIgital Heritage, write to us at info@museumofbritishcolonialism.org or tweet us @museumofbc. We’d love to hear from you and hear your thoughts on this.